Posted by Kasra

This wonderful comic had stayed in my drafts folder for a very long time and I had decided finally not to post since Calamaties of Nature had stopped publishing comics. But then again, a recent PLOS ONE paper reminded me of it again. Toxoplasma gondii is one of my favorite parasites. It is one of the most common parasites of humans and in majority of cases lays dormant throughout life, making it one of the most successful parasites in Nature. After infection (eating poorly cooked infected meat or contact with feces of an infected cat), T. gondii escapes the gut and migrates to the brain. At first glance, it does not seem to do much over there, at least nothing drastic. But studies including current work by Ingram et al. have shown that T. gondii infection can permanently alter animal behavior, permanently meaning the behavioral change stays even after infection has been cleared. This recent study is another example demonstrating this ability of the parasite:

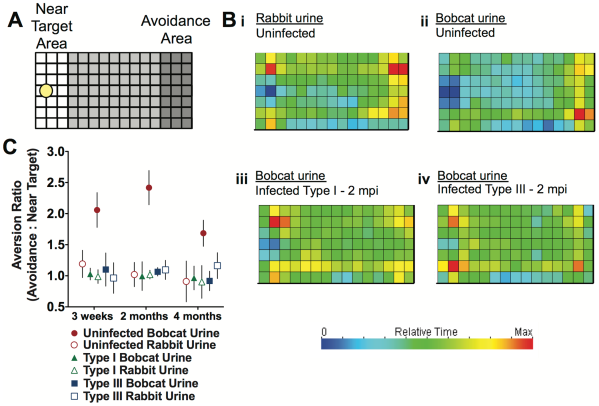

Ingram et al. checked how the behavior of an infected or uninfected mouse differ when exposed to predators, in this case Bobcat urine. As you can see in the figure below (Part A), they set up a field, one part of which was spotted with Bobcat urine or Rabbit urine (controlling for effect of just urine versus predator urine). Infected, uninfected and infected with a attenuated parasite (which could successfully clear the infection) mice were let in the area to see which spots they spend more or less time at, translated to which areas they avoid and which areas they do not. As you can see in sections Bi and Bii, the mouse partly avoided the section with rabbit urine (hence the importance of controls!) but this avoidance was way stronger when exposed to Bobcat urine. Surprisingly this behavior almost vanishes in infected mice, regardless of the strain, in other words, regardless of presence or absence of parasites in the brain.

There is a body of research on possible effects of T. gondii infection on human brain and behavior and correlations to increased suicide and schizophrenia have been suggested, although not confirmed. Still we all keep in mind that correlation does not mean causation.

Could this alteration of animal behavior also have an evolutionary explanation/impact on Toxoplasma’s life cycle? In other words, is there more to this phenomenon than just parasite infects brain, brain acts strange?

There is a difference between cats (big and small, domestic and wild) and the rest of the animals when it comes to Toxoplasma. In other animals, as I mentioned above, Toxoplasma escapes the gut after ingestion and moves to muscle and brain tissue and just stays there. So basically the infection is kind of a dead-end. It cannot be transferred to the next host until the current host dies and gets eaten up by another one. However,cats are the main hosts for Toxoplasma. That is where the parasite goes through the sexual stage of its life cycle. Also, Toxoplasma cysts are constantly shed from an infected cat through its feces. Not a dead-end infection. Now the loss of predator in Toxo-infected mice makes sense! It helps the parasite get back to its main host where it can complete the cycle! This is a trait that would have been highly favored by natural selection whenever it evolved. Because it would strongly increase the chance of the parasite being passed around to the next host.

At the end, what the comic made me think of was, could those parasites also have parasites that would alter their behavior in their own benefit? Is this is a classic example of the Extended Phenotype idea introduced by Richard Dawkins?

Reference:

Ingram WM, Goodrich LM, Robey EA, & Eisen MB (2013). Mice Infected with Low-Virulence Strains of Toxoplasma gondii Lose Their Innate Aversion to Cat Urine, Even after Extensive Parasite Clearance. PloS one, 8 (9) PMID: 24058668